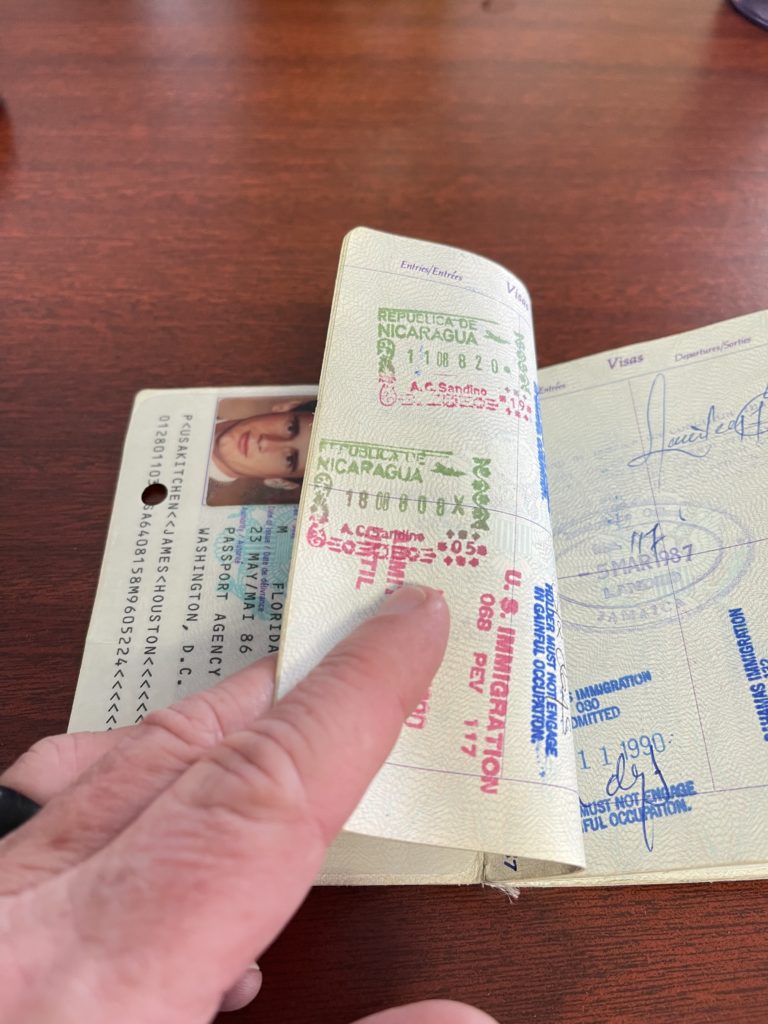

I traveled to Nicaragua in 1986, during the Contra War.

This was another proxy war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. On one side of the conflict were Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, Soviet puppets or sympathizers. On the other were the rebels, known as the Contras, who the U.S. hoped would remove the Sandinistas from power, supported by the Reagan presidential team.

Jim’s Perspectives:

I had a chance to spend 2 nights in Managua, and then spent 3 nights in rural Nicaragua. This was an eye-opening experience for a me, being relatively new to international travel. I stayed two nights with a family in a very basic grass hut, which was maybe 100 square feet. It had no electricity nor did it have running water. I slept in the family’s hammock, while they slept on the floor. The father got up every morning at 4am, and spent the entire day cutting sugar cane in the scorching hot sun. I was struck that none of the children in the village wore shoes. This was my first realization that money did not equate to happiness, because everyone seemed happy and content, despite having “little”.

Here is an excerpt from my (upcoming) book about Nicaragua:

“One of my most formative travel experiences as a young man was a trip to Nicaragua. This was in the 1980s, during the war between the contras and the Sandinistas, essentially a proxy war between the US and the perceived threat of Soviet influence in the Western hemisphere. Like most of the internal wars in Central America, there were no real good guys. Most of the people lived in the middle, neither supporting their governments nor supporting the rebel forces opposed to them. They just wanted to work and live in peace. The war in Nicaragua would cost 30,000 lives.

As part of an international cultural exchange, organized by a church in Mexico in the hopes of bringing the war to an end through citizen diplomacy, I was fortunate to be able to stay in a remote village a hundred or so miles from the capital city of Managua. When I arrived, I was staggered by the poverty and dismal living conditions. My host family of three—a father, mother, and three-year-old boy—lived in a rural area in a rudimentary mud hut that was maybe seventy square feet at most. There was no electricity, no running water, and no toilet. The family insisted that I sleep in the hut’s single hammock, which was strung from one side of the hut to the other, while they slept on the floor. But sleep was hard to come by. It was unbearably warm and humid at night, and our hut sat next to the ten-foot-high sugarcane fields, filled with grasshoppers whose collective chirping was louder than the string section of the Nicaraguan National Orchestra.

Every morning, the father of the house, a tall, slender man who was thirty but looked fifty, awoke precisely at four o’clock, helped by the dependable sound of the roosters crowing. Off to the sugarcane fields he would go, to work all day in the blistering sun, finally returning to the hut in late evening. His income provided for the food in the household, but there was nothing much else.

After a few days of staying with the family, I decided to explore the nearest town, about an hour or so away. Transportation was via chicken bus, a common mode of transportation in Latin American countries. Chicken buses are typically retired school buses from the US, colorfully painted and crammed with passengers the way a truckload of chickens might be crammed together, hence the name, although another explanation might be that it’s quite common to see passengers carrying chickens with them to the town market. Either way, I hopped aboard the chicken bus for the bumpy ride to town.

Quickly, I saw that the town was no more affluent than the village where I’d been staying. In fact, it seemed like just a larger, busier version of it. The huts were similar and also lacked plumbing and electricity. I saw no one wearing shoes as they walked down muddy streets. I found myself feeling pity for these people, fortunate that my life afforded me so much more.

As I took in the scene, observing the privation and hardship, I suddenly heard the laughter of children. Turning, I saw a girl and two boys, maybe five or six years old, running barefoot in shorts alongside an old bicycle tire that they were rolling along beside them, giving it a spin every time it began to wobble. Sometimes they’d get in each other’s way and trip themselves, landing in a collective heap, the tire falling along with them. This resulted in more laughter and in a moment, they were back up and rolling the tire again, chasing it down the dirt road.

Strange, I thought. Didn’t these kids understand? Didn’t they see the poverty that was, to me, so clearly in evidence? They lived in grass huts with no electricity or running water. They had no bathrooms. They slept in hammocks or on matts on the floor. They had very little to eat. They wore dirty clothes and had no shoes. Later, back on the chicken bus, I wondered how they could have missed it. Finally, I decided that the kids would have seen what I saw if they hadn’t been so distracted by their laughter and fun.”